Traditional zoning, the practice of dividing communities into separate use districts, has become widely accepted across the United States since its introduction more than eighty years ago. Zoning has become so pervasive in the United States that, for the general public, zoning is community planning. For many planners, however, the traditional zoning ordinance is a dysfunctional community-building tool.

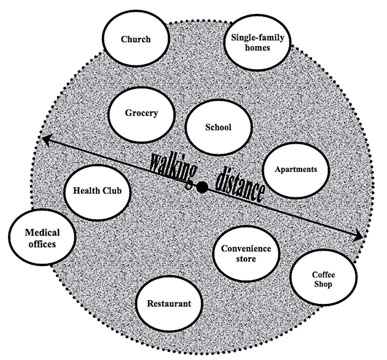

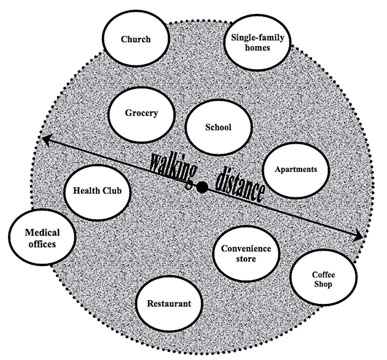

"The basic tenant of traditional Euclidean zoning is that the solution to all land use problems is spatial: Segregation of land uses into large single-use zones, minimum lot sizes and setback requirements." (Cortright) The result is that compatible living, working, shopping, recreating and worshiping activities that should be in close association to one another are instead widely separated, forcing people into cars and inhibiting face-to-face contact.

The nature of where we live and work affects our sense of self, how we interact with other people and even our ability to function as citizens in a democracy. Christopher Alexander, author of A Pattern Language,(2) has advocated a comprehensive change in the nature of zoning to effectively redistribute workplaces throughout a community, and to discourage large concentrations of workplaces without family life around them. Under Mr. Alexander's zoning scheme:

To accomplish this, planners must seek to change the heart of zoning, which is the separation of uses into zoning districts. For some in the planning profession, single-use zoning districts have become an immutable planning principle beyond question or re-examination. Babcock counters this pervasive belief, noting that "districting is nothing more than a legislative device that should not be insulated from scrutiny and should be discarded if it is no longer viable."(3)

Zoning was originally established as a means to segregate and control certain undesirable land uses, including industrial uses that emit odors, dust or smoke, or are sources of noise, air or water pollution. As zoning evolved towards segregation of virtually all uses from one another, industrial processes were improving to the point that, today, many "industrial" uses are clean, quiet and compatible with other community-building uses. PLACE defines as "opposing uses" those uses that cannot be placed in close proximity to community-building uses due to health, safety or welfare concerns. Examples of opposing uses include steel mills (noise, air and water pollution), trucking terminals (outdoor storage, truck traffic, noise and light pollution), sexually-oriented businesses (crime, immoral behavior), airports (noise) and intensive livestock operations (odor, insects, water pollution). Under the PLACE zoning concept, opposing uses would be required to be set back a minimum safe distance from other uses that would be impacted by the opposing use.

![]()

Brief history of zoning

Legal aspects of zoning